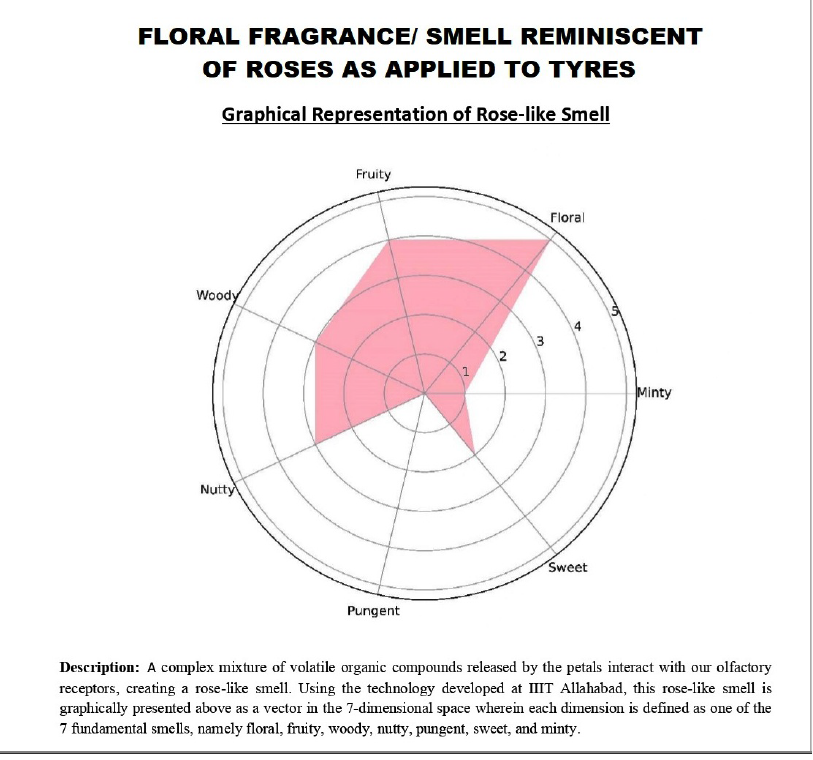

The Indian Trade Marks Registry has accepted its first olfactory (smell) mark. It is trade mark application no. 5860303 filed by SUMITOMO RUBBER INDUSTRIES, LTD with the title: “FLORAL FRAGRANCE/ SMELL REMINISCENT OF ROSES AS APPLIED TO TYRES”. What got this application over the line to acceptance – other than the smell of roses as applied to tyres being distinctive – is that it provides a seven-dimensional olfactory graph which plots the rose scent across seven olfactory axes. Pretty neat! Below is the graph for you to see for yourself:

Description: A complex mixture of volatile organic compouns released by the petals interact with our olfactory receptors, creating a rose-like smell. Using the technology developed at IIIT Allahabad, this rose-like smell is graphically presented above as a vector in the 7-dimensional space wherein each dimension is defined as one of the 7 fundamental smell, namely floral, fruity, woody. nutty. pungent, sweet, and minty.

What determines whether a smell can or cannot be registered as a smell mark? The Sieckmann case in the European Court of Justice (ECJ) is often referred to as the answer. In the Sieckmann case, the applicant filed for "methyl cinnamate" scent and provided in support were its chemical formula, a written description ("balsamically fruity with a slight hint of cinnamon"), and a sample of the scent. The ECJ set out seven representation requirements for trade mark registration: (1) clear, (2) precise, (3) self-contained, (4) easily accessible, (5) intelligible, (6) durable and (7) objective. Over and above these requirements, the sign was required to be suitable for graphical representation. The ECJ therefore ruled: (A) a chemical formula was not sufficiently intelligible, sufficiently clear or precise; (B) a written description was not sufficiently clear, precise or objective; and (C) a physical deposit of a sample of the scent was not a graphic representation and not sufficiently stable or durable.

The first smell mark reportedly registered by the United Kingdom (UK) was substantially the same as the one accepted by the Indian Trade Marks Registry, as it read: “The trade mark is floral fragrance/smell reminiscent of roses as applied to tyres”. While no longer active on the UK Trade Marks Register, we can provide an example of an active smell trade mark registration on the UK Trade Marks Register, namely, trade registration no. UK00002000234 which itself reads: “The mark comprises the strong smell of bitter beer applied to flights for darts”.

The Australian Trade Marks Register has quite a selection of smell marks, although most, unsurprisingly, have not been accepted. An exception is trade mark registration no 1241420 which is described as follows: “The mark consists of a Eucalyptus Radiata scent for the goods” registered in respect of golf tees (the thing that holds up the golf ball). Another registration located on the Australian Trade Marks Register is trade mark registration no 1858042 which reads: “The trade mark is a scent mark. It consists of the smell of cinnamon (being principally Cinnamaldehyde) applied to non-wood-based furniture as outlined in the specification of goods”.

On to the South African legal standard, The Trade Marks Act 194 of 1993 defines a “mark” as “any sign capable of being represented graphically, including a device, name, signature, word, letter, numeral, shape, configuration, pattern, ornamentation, colour or container for goods or any combination of the aforementioned”. Although the word “smell” doesn’t appear in the definition, the story doesn’t end here, as the list provided is a non-exhaustive one. What is not open to debate is that a trade mark in South Africa must be “capable of being represented graphically”. And South African trade mark law has not shied away from the issue: The Registrar of Trade Marks in January of 2009 issued “Guidelines with regard to the lodging of non-traditional trade marks” which specifically include guidelines on olfactory (smell/scent) trade marks under the heading “H. Olfactory (Smell/Scent) Marks” which reads:

• with regard to representation, at the least a written description of the mark will be required

• any other conditions as may be required for purposes of examination of the mark, e.g. specimen of the mark, may be required by the office

• the “Sieckmann criteria” will be applicable in relation to marks of this nature – it must be clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective

There are some examples of smell trade marks on the South African Trade Marks Register, one being a registration for a smell mark described as follows: “The mark comprises the strong smell of bitter beer applied to flights for darts”. Sound familiar? While the mark proceeded to registration in 1999 (prior to the guidelines) it has since been removed, but due to being unpaid, and so there is no reason to suspect that cancellation proceedings were involved.

We also note trade mark application no. 2000/07992 filed by RECKITT & COLMAN SOUTH AFRICA (PTY) LTD with the title: “A LEATHER FRAGRANCE/SMELL AS APPLIED TO POLISHES”. This too has not proceeded to registration. Last of which on my list, and a more recent example, is trade mark application no. 2009/08789 which is described as follows: “The trade mark applies to manures and fertilizers having a coffee scent”. As a coffee-addicted lawyer, I do not object to the idea! While the mark is longstanding as an application, there are at least fair prospects of registration. I believe that the manner of depicting a smell graphically as was done in the Indian trade mark case referred to above will assist to mainstream smell marks, and we will "snuff out” any further developments.